“I Really Do See the Bronx as a Second Ghana”: An Interview with Afua Ansong, Author of Black Ballad

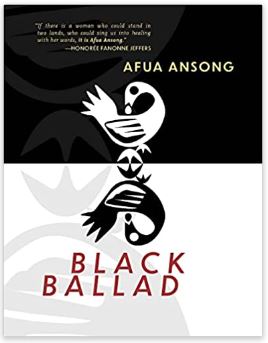

A postdoctoral scholar and artist at Mount Holyoke College, Afua Ansong was raised in Accra, Ghana and the Bronx. Her recent chapbook, Black Ballad (Bull City Press, 2022), explores Black female experience and Ghanaian identity in New York City. Ansong is also the author of Try Kissing God (Akashic, 2020), published as part of the prestigious “New-Generation African Poets” series edited by Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani, and American Mercy (Finishing Line Press, 2019). This spring, The Literary Bronx research seminar at Lehman College had the chance to sit down with Dr. Ansong to discuss her forthcoming chapbook, her craft, influences, and more.

The Literary Bronx: The book’s first poem ends with these two intriguing lines: “Poetry does not save me, / but how can this be? But how can this be?” Tell us a little about your own development as a poet.

Afua Ansong: I don’t think there’s ever been a time I haven’t possessed a poetic perspective about my life, about the ways in which I consider myself a Black woman, an African woman, a Ghanaian woman, a woman from the Bronx.

When I moved from Ghana to the United States, I settled in the Bronx. My mother lived here and the Ghanaian community here is larger than in other communities outside New York. I felt like the only way I could respond to this new space was to write. My aunt gave me a notebook, and I would come home each day and write down all the differences in the American education system, the way that, during recess or lunch breaks, for example, the students stayed inside. I was coming from a place, in Ghana, where during recess we would go outside and play, and here, it’s like America keeps you so boxed in, and I didn’t understand this new concept of freedom.

When I tasted the school milk, it had a watery consistency. I was used to evaporated milk in Ghana, which is thicker. Sometimes I would speak in class and my friends would say, “why do you sound like that?,” and I would tell them, “Everyone in my country sounds like this, why do you all sound like that?”

Searching for the language to make meaning of this new place is what I believe led me to poetry. I began to form thoughts of myself, and theorize ways in which I could be Afua, I could be this young Ghanaian girl and still not be afraid of America. It wasn’t easy, but poetry helped me.

TLB: One of the poems in the book has this really polemical title—“I am Not African.” We had a little debate going on about what you meant by it. Were you clarifying that you’re African but want to be identified more specifically, by nationality, for example, or were you rejecting this big, pan-ethnic identity category altogether?

Ansong: I’m being a little sarcastic here, because obviously I am African. But the title of the poem comes from being referred to constantly as an African. “Oh, you’re African.” I would respond with, “No, I’m Ghanaian, or I’m Ghanaian American.” Africans are very competitive: for example, Ghanaians and Nigerians say they have the best jollof rice, or you’ll get the debate of one nationality saying they are better than the other—we have a lot of pride, positive pride. I am not ashamed of being African: I just wanted to specify, to say I am West African, or I am Ghanaian.

On a more literary note, this poem was inspired by two texts. One is NoViolet Bulawayo’s novel We Need New Names. She’s a Zimbabwean writer. The other is a poem called “Telephone Conversation” (1962) by Wole Soyinka, a Nigerian poet. In We Need New Names, there is a character, Darling, from Zimbabwe who moves to the United States, and I’m thinking of the ways in which she grapples with her new identity. In “Telephone Conversation,” the speaker is having a conversation with a landlady in London, and the landlady asks the speaker, “What is your color?,” signifying his race. It seems the landlady is not willing to give the apartment to a person of color, so the speaker describes the color of his skin as “West African sepia.” In my poem, I say I’m not even “West African sepia.” I wanted to push beyond the boundaries of putting us all together on one continent and saying we are all Africans; that was the main idea.

TLB: Your response really illustrates the rich intertextuality that a reader can glean from your work—perhaps unsurprising given that, in addition to being a poet, you are also a scholar of African diasporic literatures. Can you tell us a little bit about how your scholarly work has shaped your poetic practice? For example, one of the intriguing features of your book is its incorporation of Adinkra, the traditional symbols used to express proverbs and concepts in Ghanaian culture.

Ansong: When I first thought about my research focus, the African woman or the Black woman came to mind. I started by reading fiction written by other African women or Black women that talked about the challenges that African women coming to the United States, or even those who already lived on the continent, face, but I would respond to these texts by writing poems. Even in my doctoral dissertation where I explored the poetics of Adinkra symbols, I’m looking for ways in which African women, or Akan women specifically, are represented in these symbols. I’m looking at the proverbs that talk about African women, I’m looking at ways in which the symbols first came to the United States, and I’m looking at the kind of people that popularized the symbols in current-day America. I am constantly asking the question: What does it mean for the African woman to have these symbols and what does it mean for the African woman to be able to tell her story as an immigrant in the United States?

African women’s voices are marginalized. We don’t hear a lot from them, and so it’s important for me as an African woman to be a literary conduit and poetic representative.

TLB: In an online video titled “Afua Ansong Reads her Poem ‘Mother,’” which you recorded while working on your doctorate at the University of Rhode Island, you talk about the different Englishes you use as a Ghanaian American. In a poem from Black Ballad, you write, “the texture of language reminds you, you are not home.” Could you talk about how you deploy these Englishes and other forms of code-switching in your poetry for aesthetic or political purposes?

Ansong: I was recently a featured reader on Church of Poetry on Twitter Spaces organized by Henneh Kyereh Kwaku, a Ghanaian poet, and most of the people there were from Ghana. I noticed that when I was pronouncing some words, I let the American accent go because, you know, that didn’t feel like home. So with a poem like “Things You Left in Accra before Moving to the Bronx,” when I got to the last part and read “Asaana, Yooyi, Aluguntuguin,” the intonations changed because I felt very much at home with my Ghanaian audience.

But I also feel like being able to code-mesh is beautiful in itself. It gives me the sense of power to be able to say, I can do this, I can do that. Speaking another language means you have the ability to move through different spaces.

In terms of my writing process, I hardly think in Twi, which is the local Akan language I speak. I think in English. I’ve actually lost a lot of vocabulary from my mother tongue and I am often corrected by my mother. In Black Ballad, for some of the symbol poems like “Odo Nnyew Fie Kwan,” I intentionally include the Akan proverb. It’s spelt out in Twi and then translated into English because I want you, as a non-Ghanaian, to pronounce it, I want to invite you into my very Ghanaian space and let you know that this girl is not just, you know, from the Bronx, this girl is from the Bronx and from Ghana and from Rhode Island and from all these different spaces. When Ghanaians recognize these symbols, they’re pulled in and are able to feel this sense of familiarity.

TLB: Still on the topic of language, we wanted to ask you a question about English. English is one of the official languages in Ghana, but it’s also, of course, a colonial language linked to the British Empire. Could you speak to us about how you negotiate that fact in your art?

Ansong: I speak English since I received formal education in that language, and I really didn’t think about colonization much until I came here. I feel a little privileged because I can switch between Twi and English, and I hope that, in the future, as I continue to publish, I can bring more aspects of Ghana and its local languages into that international space, so that my readers have an anti-colonial experience when engaging with my work.

TLB: Thinking about recent US history, many or most of these poems must have been written during the time of the George Floyd Uprising and Black Lives Matter movement. How did writing during this time influence your work?

Ansong: In a poem like “Counting Bodies,” I’m thinking about the loss of Black boys in this country. Although the theme of the book focuses on African female subjects, or the Black woman subject, these Black women give birth to Black men, right? I know it is not always obvious, but we must preserve what she births.

What is the song of the Black woman who finds herself an immigrant in the United States?

When I saw these boys—who were the inspiration for the poem—on the Bx19 bus, I did not think about anything but the preservation of their lives, what it means for Black boys in the Bronx to be preserved and not to be shot the next day, and internally, I really prayed in my heart that they would stay alive.

A poem like “Rebellion,” which I wrote in 2016, talks about the Trump presidency and how that really affected immigrants and people of color. Because I’m an immigrant and I know what it means to be treated as an outsider—I’ve lived in America since I was a teenager—it was easier to channel these experiences as poetic responses to the political implications of being Black and an immigrant in this country.

TLB: When did you know you would call the collection Black Ballad? Should we see the title as a response to, or anchoring in, this cultural moment of Black protest?

Ansong: The initial title of the collection was Postcard to Phillis Wheatley Peters, which is the fourth poem in the book. Phillis Wheatley Peters was one of the first African-American, enslaved writers known to publish in the United States. She was brought from the Senegambia region to the United States when she was about 11 years old. I saw her as more of an African poet than an African American poet, and she reminded me of myself. In the title poem, I imagined that if Phillis Wheatley Peters was alive today, I would tell her about all of the issues going on in our country, the struggles of being an African immigrant poet, her knowing so well what that meant and still being able to express herself.

In 2020, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, who was generous enough to blurb my book, published a really huge volume of poems about Phillis Wheatley Peters called The Age of Phillis, so it felt redundant to put out another book with a similar title, and my collection centered African female subjects more than it centered Wheatley Peters. I thought about Black Ballad as the song of African women, the song of African women in America who seek to redefine their identity and what that song sounds like. A ballad is a form of poetry, and although none of the poems in my book take the form of the ballad, the theoretical inspiration is: what is the song of the Black woman who finds herself as an immigrant in the United States?

TLB: Let’s talk some more about the strong current of women-of-color feminism in Black Ballad. These poems, like your earlier work, pay homage to literary foremothers, such as the poet Lucille Clifton. What have these figures meant to you as a writer?

Ansong: Lucille Clifton has been such a blessing. Three of the poems in this collection build on forms she has written in. “Rebellion” is from her poem titled “won’t you celebrate with me.” “Foreign City” follows a similar format to one of her older poems. “Lineage: Conversation with A Literary Mother” is also building off themes she has written about.

Clifton is someone I admire a lot because she has these really dense, short poems. If you haven’t read Clifton, I would encourage you to go get her collection edited by Kevin Young and spend the summer reading her. I felt that she was doing the kind of work in terms of craft choice that would guide me in self-expression. She goes straight to the point, uses images in very short lines, and then she’s done, and moves on to the next poem. She taught me ways in which I could be brief and impactful.

I thought it would be a great honor to bring her into—to invoke her in—my work. There are very few women of color, or even Black women, who are recognized as poets in this small creative space, so I wanted to introduce the reader to Lucille Clifton. This was my invitation to say, “Welcome, mother, literary mother,” but also, “if you haven’t already read Lucille Clifton, this is the time to do so.”

TLB: Still on the topic of the strong vein of Black feminism that runs through your poetry, what is the message to girls back in Accra, to girls here in the US?

Ansong: I think one thing that has been on my heart to do is to find ways to promote creative writing and creative expression to young women in the US and especially in Ghana. Becoming a poet is not really prestigious or heavily encouraged in the Ghanaian community.

But I believe that creative writing really teaches you ways to own your voice and to express yourself, and even to build yourself, right, so I feel that the confidence that I have as an individual is because I was able to write constantly and become intimate with my voice, and that’s a tool I want to share with young girls. You can own your voice.

TLB: It’s time we zero in on the Bronx. You’ve already spoken of the borough as home and the culture shock you experienced upon arrival, that sense of being “boxed in,” as you put it earlier. In your poem “Foreign City,” you write beautifully of “the surprise of morning / over the gossiping mango trees” in Accra. What surprises did the Bronx hold for you as a young woman and emerging poet? Does the Bronx also have its beauty? Is it one you feel like you’ve articulated yet as an artist?

Ansong: I really do see the Bronx as a second Ghana. I’ve lived on Long Island and in Rhode Island, but I always come back home, which is the Bronx, to get my goat meat. Because those other places don’t have goat meat the way I like it. The Bronx feels like home in an authentic way. The buildings are all crowded together. Your neighbors are from all these different places. You greet your neighbors, and they are inquisitive about your personal life. You can hear what’s going on in their apartment.

The Bronx holds a sense of home for me in a way that Ghana cannot, because Ghana is a flight away but I can take a train from Rhode Island to the Bronx in three hours and I would be home: I could be with family and speak my mother tongue, I could go to the bodega that I missed. There’s so many ways when I’m outside the Bronx that I’m reminded that I’m not in the Bronx, and I’m like, oh, I can’t wait to go back home, I can’t wait.

I really do see the Bronx as a second Ghana. The Bronx feels like home in an authentic way.

TLB: Still thinking about your home borough, we loved the line in your poem “Your First Time in America” that observes that “America hides its ugly with lights.” In one sense, the line is paradoxical, because we think of darkness, not light, hiding things. But it reminds us too of the ways that New York City—perhaps the Bronx is an exception—is so glamorized by those who don’t live here. Do you think it’s possible to write about New York without glamorizing it in this way, without hiding its ugly with lights?

Ansong: When I wrote this poem, I thought about the first time I saw America, and it was the typical way in which it’s glamorized. I came at night, and just going over the bridge and seeing all the lights with their grandeur, it seemed as if I had entered heaven. Coming from Ghana, I had never seen so many lights at once in my life. I thought, “How can this country afford this?” In Ghana, we have this thing called “Light Off,” where we just lose power, and then we have to use lanterns or candles. Sometimes you lose power for three days, and then it’s back on without any warning. I didn’t grow up with a generator, so I learned to listen to my grandmother’s stories during the darkness. These lights of New York really blurred my vision.

America has a way of using lights to hide its problems. I was convinced initially from the lights I saw that it was a beautiful place. When we got to the Bronx, I was like, they played us, right?

TLB: Your book is being published in Bull City’s “Pay What You Want” series designed to make poetry books more available to readers of all backgrounds, something we find really exciting. Tell us how this promotion is meaningful to poets, and how it might help your book reach a wider audience.

Ansong: A lot of times, people are scared of poetry. When people know that they can pay any amount they suggest for something that may scare them off, the cost doesn’t become a barrier. They’re able to concentrate more on enjoying the book. I am really excited to see new audiences develop a newfound love for poetry.

TLB: Final question. Do you have a favorite poem in Black Ballad? Is there a poem that maybe hasn’t stood out as much to early readers of the book, that’s kind of understated, but for which you have a special affection? Could you tell us why?

Ansong: “Unidentified” is one of my favorites, I would say. What I love about this poem is that it really situates the speaker at the peak of my research on the Adinkra symbols. I traveled to UCLA to explore an archive of the symbols held at the Fowler Museum, and at the time I was concerned about the trajectory of my research. There were several moving parts to the project that I was still finetuning. As a researcher, you wonder if you will find the answer to your questions.

Take the line, “the Sunday afternoon / I avoided a snake that almost bit me.” This was something that actually happened during my childhood in Accra. I was going to see a friend, and I was nearly bitten by a snake. The poem works as a form of resurrection for me as a scholar and poet who dared to leave the Bronx and come to Rhode Island to say, “I want to be a scholar and I want to be identified, I want to find my place in this world.” Thinking of the many Adinkra symbols in the archive that were labeled unidentified because no one can trace their names, no one can trace where they came from, thinking of myself, or even of Phillis Wheatley Peters, or of many of my ancestors who couldn’t return home because they didn’t know how to, or of many African Americans who are seeking ways to reconnect with lineage, this poem holds value. A lot of readers don’t—aren’t—as drawn to it as I am, but it’s one of those poems that really comes from a special place.

TLB: Thank you, Dr. Ansong. We’re excited to see Black Ballad in print this summer and look forward to continuing to follow your career at The Literary Bronx.

To order a “pay what you want” copy of Black Ballad, click here.

To order a signed copy from the poet’s website, click here.

This interview was conducted by members of the Spring 2022 honors seminar in Bronx literature at Lehman College: Enera Celic, Nellie Featherstone, Pilar Guerrero, J. Bret Maney, Abada Rakib, MJ Robis, and Moesha Williamson.

Featured image courtesy of Hanspiere.